Research Article

Research Article

Bio-Psycho-Social Burden of Patients With Fibromyalgia – Results of A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Depersonalized Data Provided by the German Pain E-Registry

Michael A. Überall1*, Heinrich Binsfeld2, Dorothea Fago3, Thorsten Lücke4, Silvia Maurer5, Norbert Schürmann6 and Johannes Horlemann6

1Private Institute of Neurological Sciences – IFNAP, Center of Excellence in Health Care Research, Nordostpark 51 90411 Nürnberg, Germany

2Regional Pain Center Ahlen, Kirchplatz 7 48317 Drensteinfurt, Germany

3Regional Pain Center Gießen/Pohlheim, Neue Mitte 12 35415 Pohlheim, Germany

4Regional Pain Center Linz, Magdalena-Daemen-Str. 20 53545 Linz am Rhein, Germany

5Regional Pain Center Moers, Asberger Str. 4 47441 Moers, Germany

6Regional Pain Center Kevelaer, Grünstrasse 25 47625 Kevelaer, Germany

Michael A Überall, MD, Private Institute of Neurological Sciences – IFNAP Center of Excellence in Health Care Research, Nordostpark 51 90411 Nürnberg, Germany.

Received Date:August 05,2024; Published Date:August 26, 2024

Abstract

Background: Fibromyalgia is a common pain syndrome (FMS) affecting 2-4% of people worldwide, characterized by chronic widespread pain

in combination with heterogeneous symptoms interfering with physical, mental, and emotional dimensions of existence that often lead to reduced

functioning, work productivity and quality of life. Although highly effective diagnostic tools exist, a significant proportion of patients is neither

adequately diagnosed nor their disease-related burden recognized. The aim of this study was to evaluate the bio-psycho-social burden in patients

confirmatory diagnosed via the revised 2016 diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR).

Methods: Identification and biometrical characterization of patients with FMS based on depersonalized routine data of the German Pain

e-Registry (GPeR).

Results: Through the application of the revised ACR criteria, 15,211 patients (4.6%; 85.7% female; age 55.5±11.4 years) of the GPeR were identified

to suffer from FMS since 16.3±14.2 years. Reported lowest/average/highest 24-hr. pain intensities were high (40.4±22.6/60.9±18.8/81.3±16.1 mm

VAS) as well as FMS-related disabilities in daily life with 64.7±18.2 mm VAS in the modified pain disability index. Physical/mental quality-of-life

assessed with the VR12-PCS/MCS were significantly impaired (27.9±6.9/37.9±11.1). 40.4/47.7/27.7% of these patients documented moderate

to extreme depressive/anxiety/stress symptoms on the DASS-21, 40.7% (n=6,187) reported these problems simultaneously in all three DASS-21

dimensions, and 11.3 respective 4.4% of those affected stated that they regularly or frequently thought about suicide due to the long-lasting severity

of their FMS symptoms.

Conclusions: FMS is not only a common and cost-intensive chronic pain condition, but first and foremost a complex health disorder that

severely impairs quality of life and participation in daily life activities of those affected. Despite effective phenomenological diagnostic criteria

that are easy to apply even under routine conditions, the diagnosis (crucial for any rational treatment strategy), is still not made in every case and

regularly too late, despite typical clinical symptoms.

Keywords:Fibromyalgia; Chronic Widespread Pain; Diagnostic Criteria; Symptom Severity; Bio-Psycho-Social, Burden; Quality-of-Life; Depression;Anxiety; Stress; German Pain E-Registry

Background

The Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS; from Latin fibra for ‘fiber’, and “myalgia”, which stands for muscle pain from ancient Greek μῦς mŷs) - more accurately referred today as “chronic widespread pain syndrome” (CWSP) - is a common syndrome of widespread pain in various parts of the body in combination with sleep disorders/ insomnia, morning stiffness, reduced physical and mental performance, as well as increased fatigue, depression, anxiety, and stress that persists for at least 3-6 months [1]. CWSP affects between 2 to 4% of the general population in industrialized countries of the Western world and is predominantly observed in women, which are affected in 6-9 of 10 affected persons [2,3]. CWSP has an important impact on the physical and mental quality-of-life and is – beyond that - associated with high socioeconomic costs to the health care system (physician visits, specialist consultations, diagnostic test procedures, pharmacological as well as non-pharmacological treatments, inefficient use of health care resources) and to the workforce (reduced work productivity, sick leave, disease-related inability to work and early retirement) for/through those affected [4-6]. In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published the first diagnostic criteria for FMS, which required a pain pressure of up to 4 kg/cm2 at 18 different body sites, with at least 11 of these sites requiring pain to be triggered by the application of pressure in order to make the diagnosis [7]. A concept heavily criticized due to the difficulties in applying pressure algometry and its rather limited validity in daily routine care, which was replaced by the ACR in 2010 with a new proposal based primarily on the use of two phenomenological scales – the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and the Symptom Severity Scale (SSS) - the severity of which is required to be constant for at least three months [8]. These criteria were revised again in 2016 and are now based on four different parameters that must be fulfilled for the confirmatory diagnosis of CWSP: (i) widespread pain, defined as pain in at least four out of five body regions; (ii) symptoms present at a similar level for at least 3 months; (iii) WPI ≥7 and SSS score ≥5 (or WPI of 4-6 plus SSS score ≥9); and (iv) a diagnosis of FM does not exclude the presence of other clinically important conditions [9].

In 1992, the World Health Organization (WHO) included FMS as an independent disease in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) under the code M79.5, which led to a significant increase in diagnoses over the years and ultimately boosted the search for possible causes (and associated specific therapeutic approaches)[10]. Even though both etiology and pathophysiology of FMS remain unclear until today, scientific research led not only to a substantial improvement of our current understanding of its underlying mechanisms but also to a significant change of its classification as disease coded now as a so called primary nociplastic pain disorder (MG30.01) in the 11th revision of the ICD released on January 1st, 2022 [11].

This classification prioritizes a central pain genesis, excludes the relevance of nociceptive or neuropathic factors in the genesis as extensively as possible and emphasizes the importance of psychological and social factors. Contrary to the long prevailing assumptions, fibromyalgia is not an inflammatory (nociceptive) disease, but primarily the consequence of a disturbance in pain perception/ processing within which malfunctions of the endogenous pain control systems obviously play a central role. While the brain has long been regarded as a central processing unit that treats sensory impressions, it is now understood as an independently active organ that generates its own predictions and hypotheses of sensations as part of a process known as predictive coding, whereby the current physical and psychological condition as well as social influencing factors and individual imprints in the personal learning history are neurobiologically integrated back to early childhood. Ultimately, the brain performs a kind of compromise between virtually expected and concrete experienced/real stimuli, creating a subjective individual microenvironment within objective reality, finally leading to the holistic and detrimental FMS – even without any specific neuronal inputs from the periphery [12-16].

Study Objective

Although the development of increasingly precise (and easier to apply) phenomenological diagnostic criteria has continuously facilitated the identification of those affected, FMS is still not recognized with sufficient certainty by a considerable proportion of general practitioners, but also by numerous specialists. At the same time, many of those affected by FMS still find it very difficult to adequately express the considerable extent to which they are physically, mentally, and emotionally affected or to be sufficiently recognized regarding their individual impairments. For this reason, the German Pain Association has launched and financed the subsequent healthcare research project entitled “F-Type Pain” in 2021 to gain deeper insights into the biopsychosocial burden of patients affected by CWSP/FMS based on primary data from daily routine care procedures provided by the German Pain e-Registry (GPeR).

Patients and Methods

Evaluation concept

Methodologically, this evaluations formally followed the concept of a non-interventional, retrospective cohort study with a onetime cross-sectional analysis of completely depersonalized data of patients with FMS/CWSP which were recorded for the first time within a prespecified evaluation window (January 2nd, 2015, to June 30, 2021) using the standardized procedures and validated self-reporting instruments of the German Pain Questionnaire according to the quality agreement for special pain therapy defined in section 135 (2) of the German Social Security Code V).

Patients

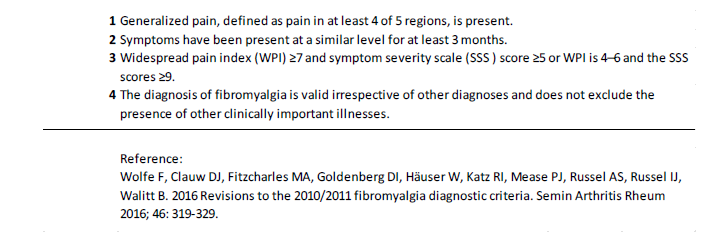

There was no formal sample size calculation for this analysis. Data sets of patients with FMS/CWSP were actively (confirmatory) identified using Wolfe’s positive classification recommendations (9) in form of the implementation of the British National Health Service (NHS)[17]) and reference to the internationally established diagnostic parameters: a) generalized pain (in 4 out of 5 body regions), b) fibromyalgia score (12 or more using the WPI (widespread pain index) and the SSS (symptom severity score), and c) a duration of symptoms of at least three months (see Table 1).

Table 1:Diagnostic fibromyalgia criteria of the American College of Rheumatology.

The evaluation was carried out retrospectively, exclusively using the data already available at the time of the cut-off date and after complete anonymization with regard to patient and institution or treating physician. In addition, the results of the evaluations were provided exclusively in the form of aggregated tables, which do not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the response of individual patients.

Data documentation

All data used for this analysis was originally routinely documented/ recorded using electronic end devices (tablets, smart phones, desktop computers) and the online documentation platform iDocLive® provided by O.Meany-MDPM GmbH as part of standard care and primarily for the purpose to improve individual patient care. At no time during these documentations was there any intervention or financial compensation in the sense of an expense allowance for any additional documentation costs associated with the use of iDocLive® or for the prescription of specific therapies.

The majority of the data reported to/stored in the German Pain e-Registry and thus available in depersonalized form for health services research was documented directly by patients using validated self-reporting instruments recommended by the German Pain Association (Germanys largest pain specialist organization), the German Pain League (Europe’s largest umbrella organization for patients with chronic pain), and the German chapter of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), the German Pain Society.

The data collection using the online documentation platform iDocLive® enables a comprehensive non-selective mapping of the patient structure treated in the participating pain practices/centers. Use of the electronic documentation platform iDocLive® was/ is free of charge for DGS members and patients, regardless of their insurance status.

Parameters of the German Pain e-Registry

The core parameters of the German Pain e-Registry based on the contents of the German Pain Questionnaire and the German Pain Diary (in the form agreed by the German Pain Association and the German Pain League)[18], and include information on the patient’s age, gender, height, body weight and body mass index (BMI), pain duration and age at first onset of FMS symptoms, pain intensity grading according to von Korff [19], stage of pain chronification according to the Mainz Pain Staging System (MPSS)[20], treatment approaches, pain intensity (lowest, average and highest 24-hour pain intensity), individual treatment goals and the so-called pain index (i.e. the arithmetic mean of the 24-hour pain intensity data; all assessed via a 100 mm visual analogue scale [VAS] with the endpoints 0 = no pain, 100 = worst pain imaginable), the extent of pain-related impairment of activities of daily living (using the modified Pain Disability Index, mPDI, assessed with the VAS comparable to the pain intensities)[21], the general and pain-related quality of life using the short form of the VR-36 Health Survey (VR-12) [22,23] its the physical/mental component subscales (PCS/MCS), depression, anxiety and stress (assessed via the Depression, Anxiety- Stress Scale, DASS-21)[24,25], comorbidities and concomitant therapies, etc.

With reference to the standardized scaled values for a) pain index (PIX), b) highest 24-hr. pain intensity (HPI), c) modified Pain Disability Index (mPDI), d) pain-related impairments in personal care and activities of daily living (mPDI-5), e) physical and f) mental quality of life (VR12-PCS/MCS), g) depression (DASS-D), h) Anxiety (DASS-A), i) stress (DASS-S) and j) suicidal ideations, a “Burden of Pain” (BoP) Index was calculated (with a possible range of values for the pain-related burden of those affected between 0=no burden and 100=maximum possible burden) specifically for the purpose of this study.

Data analysis

In accordance with the design of this non-interventional study, available data was analyzed retrospectively using explorative procedures and suitable descriptive statistical methods. The number of available or unavailable values (non-missing or missing data) was specified for all variables, irrespective of the data level. For nominally and ordinally scaled categorical data, the absolute and relative (possibly adjusted) frequencies were also calculated and cumulative values for ascending/descending scale levels were presented. Interval-scaled data were presented by specifying the mean, standard deviation, median, range (minimum - maximum) and 95% confidence interval and - where possible and appropriate - additionally grouped categorically with regard to defined cut-off values and provided with corresponding frequency analyses. All data were analyzed as reported, i.e. missing values were neither replaced nor imputed.

The optional use of biometric test procedures to compare the values between different sub-cohorts was used exclusively for posthoc assessments of the biometric significance of observed differences in frequency or expression and explicitly not for testing predefined questions and/or hypotheses. All tests used were evaluated with reference to a statistical significance level of 5% and the test procedures used were adapted to the scale level of the variables to be analyzed.

Ethics

The exclusive use of completely depersonalized data (with regard to the practitioner and data subject) and the written informed consent of all participants to the use of their anonymized data for scientific health care research projects ensured compliance with the requirements of the EU General Data Protection Regulation and national aspects of patient (data) safety. The study concept and statistical analysis plan were assessed and approved by the Executive Board of the German Pain Association. Aspects of data protection and patient safety were reviewed by the Executive Board of the German Pain League and independent data protection officers. The present work was implemented under the guidance of the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Registration

Prior data extraction and analysis, this study was entered in the online register of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for non-interventional studies (ENCEPP; EU PAS Identifier: 44365) and thus made public.

Results

Population

Based on the mirrored set of depersonalized data of 331,084 patients in the German Pain e-Registry as of June 30, 2021, a total of 15,211 patients (4.6%) were positively identified for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia/CWSP using the definitions and revised diagnostic criteria of the ACR as specified above (see table 2).

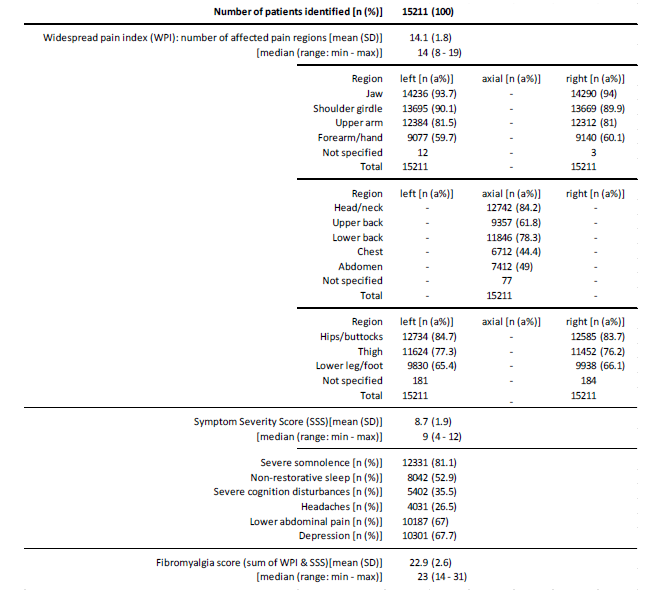

Table 2:Key figures for the diagnostic fibromyalgia criteria of the American College of Rheumatology.

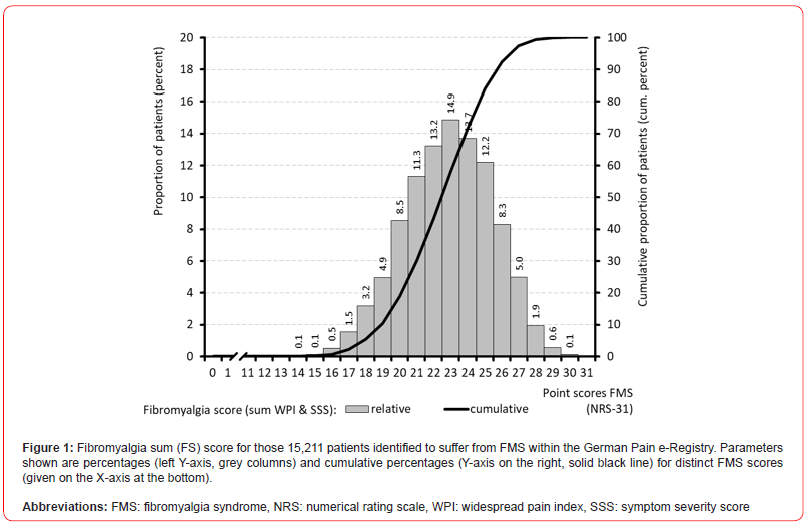

The average widespread pain index (WPI) was 14.1±1.8 (median 14, range: 8-19). Body regions most prevalently affected were the jaws (~94%), shoulder girdle (~90%), head/neck and hips/ buttock (~84%), upper arms ((~81%), and the lower back region (~78%). Bilateral involvement was more common in the upper than the lower extremity and was generally more pronounced proximal to the trunk than distal. The symptom severity score (SSS) was 8.7±1.9 (median 9, range 4-12). Severe somnolence was noted by 81.1% of patients (n=12,331), and 52.9% (n=8,042) reported non-restorative sleep. With 35.5% more than one third of patients (n=5,402) complained about severe/clinically relevant cognitive disturbances, two thirds about depressive symptoms(67.7%; n=10,301) and lower abdominal pain (67.0%, n=10,187), and every fourth (26.5%, n=4,031) about headaches. The fibromyalgia score (FS; sum of WPI and SSS) was 22.9±2.6 (median 23, range: 14-31; see Figure 1).

With 28.1% (n=4,275), nearly three out of ten FMS-patients reported FS sum scores of 25 or above, and nine out of ten (89.7%, n=13,643) sum scores of 20 or above.

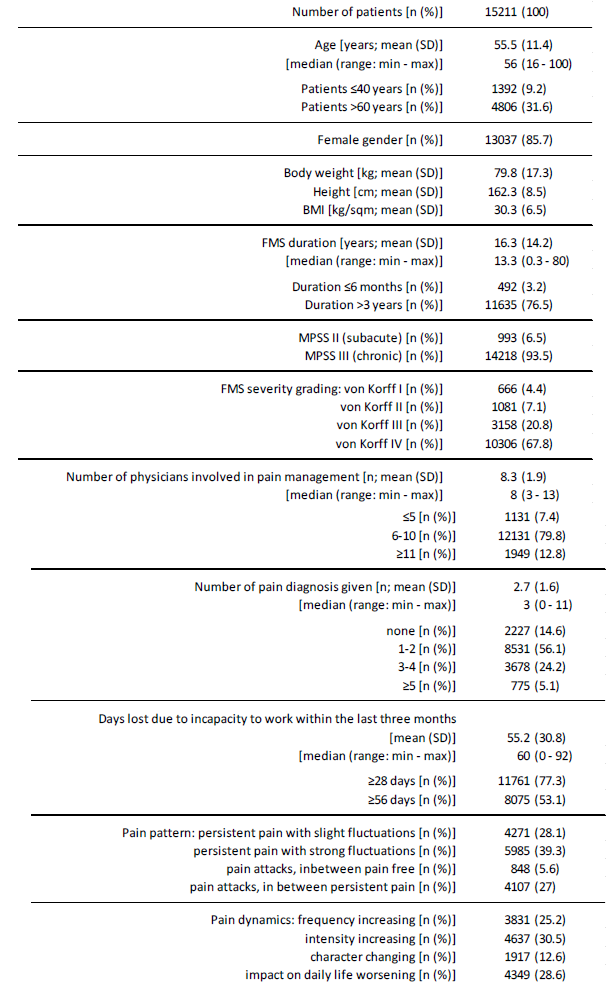

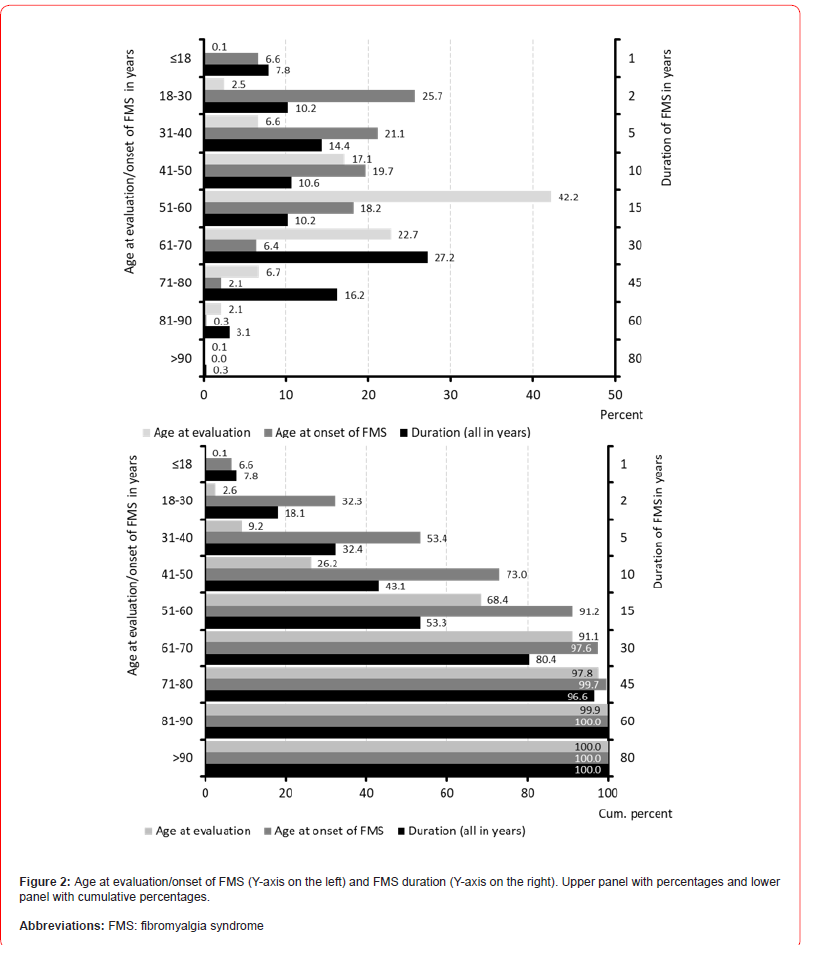

Demographic data

Table 3 summarizes information on patient demographics. Average age of patients identified with FMS was 55.5±11.4 (median 56) years, with a range between 16 and 100 years. 1,392 patients (9.2%) were 40 years or younger at the time of evaluation, 389 (2.6%) even younger than 30 years. 4,806 patients (31.6%) were over 60 years, 1,348 (8.9%) over 70 years, 335 (2.2%) over 80 years and 20 (0.1%) even over 90 years. With a total of 6,417 patients (42.2%), the largest age decade in terms of numbers was that between 51-60 years. 76.5% of patients (n=11,635) documented an FMS duration of more than three years, 15.7% (n=2,387) a duration of 1-3 years and only 4.6% (n=1,189) a duration of one year or even less. With reference to the available time data, a mean duration of illness of 16.3±14.2 (median 13.3; range 0.3-80) years could be calculated. Based on that information, the average age at first appearance of FMS symptoms was 39.2±15.0 (median 38) years with a range between 15 and 95 years. With 1,006 patients, 6.6% of the total population identified reported a first onset of FMS symptomatology during adolescence (i.e. <18 years of age), almost one third of all sufferers (n=4,909, 32.3%) documented the onset of their disease by the age of 30 (see Figure 2).

Compared to that is the number of elderly patients (i.e. those 70 years or even older) in whom FMS occurred for the first time (and persisted) in our study population significantly less (2.4%). However, the generally high number of health impairments and concomitant diseases in this age group poses particular challenges not only for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia but also for the implementation of an effective (and tolerable) therapy. In harmony with data from the literature, most patients identified with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia/ CWSP were female (85.7%, n=13,037) (see Figure 3).

Table 3:Demographic characteristics.

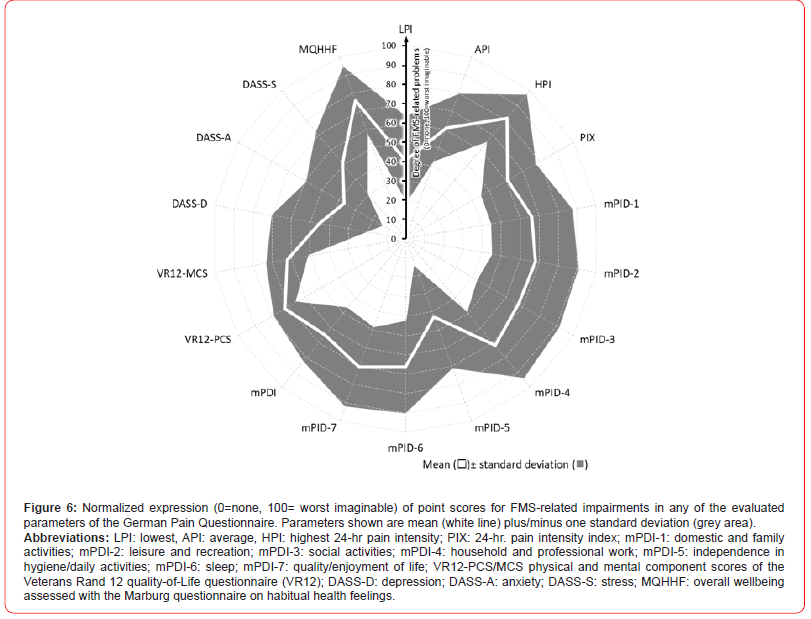

With 14,218 (93.4%), most FMS patients documented a grade III stage of chronification according to the Mainz Pain Staging System (corresponding to an advanced stage of chronification), only 993 (6.5%) a grade II stage (characteristic for a subacute status). Using the pain intensity graduation model according to von Korff, 13,464 patients (88.5%) could be assigned to the so-called “dysfunctional pain type cluster” (grades III and IV) with high pain intensities – 67.8% with extreme disability. The average number of physicians involved prior first participation in the German Pain e-Registry was 8.3±1.9 (range 3-13) and 92.6% of patients (n=14,080) reported the engagement of at least six, 12.8% (n=1,949) even those of more than 10 different specialists. In total these physicians record ed 43,048 different pain diagnoses for the 15,211 patients, with a mean of 2.7±1.6 (median 3, range 0-11, four or more in 12.2% (n=1861) and none in 14.6% of all patients (n=2,227)). The term “fibromyalgia” as diagnosis was found in 10,887 patients (71.6%). The average number of days on which patients were unable to perform their usual activities in the last three months prior to evaluation was 55.2±30.8 (range 0-92). 11,761 patients (77.3%) documented an FMS-related sick-leave within the last three months prior evaluation of at least four weeks, 53.1% (n=8,075) of eight weeks or more (see Figure 4,5,6).

The majority of the patients (n=5,985, 39.3%) documented “persistent pain with strong fluctuations” as their respective dominant pain character, followed by “persistent pain with slight fluctuations” with 4,271 (28.1%) of all mentions, “pain attacks, in between persistent pain” with 4,107 (27.0%) mentions and “pain attacks, in between pain-free” with 848 (5.6%). An overall instable pain pattern was reported by 25.2% (n=3,831) with respect to an increasing frequency, 30.5% (n=4,637) for an increasing intensity, 12.6% (n=1,917) for a changing character, and 28.6% (n=4,349) with respect to the FMS impact on daily life.

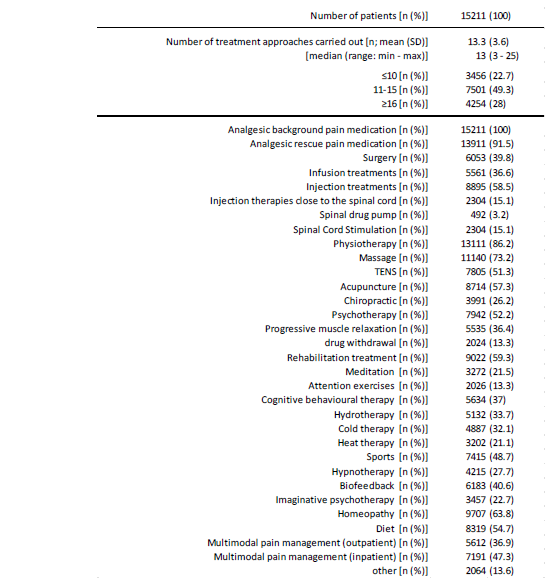

Treatment characteristics

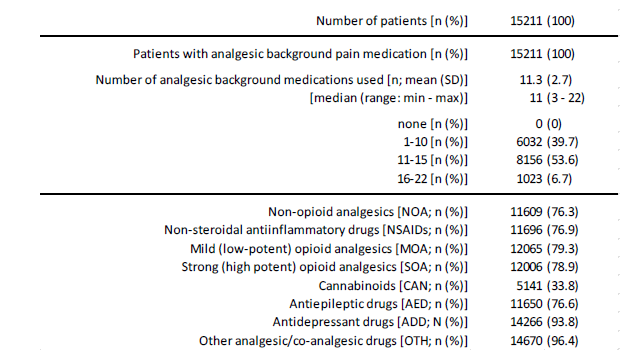

Data out of the GPeR on the treatment characteristics of the 15,211 patients positively identified with FMS are given in table 4, parts 1-3. On average, the patients documented 13.3±3.6 (median 13, range 2-25) different treatment approaches. At 28.0% (n=4,254), almost three out of ten evaluated patients documented the use of 16 or more different (pharmaceutical as well as non-pharmaceutical) treatment approaches, with 49.3% (n=7,501) every second those of 11-15 approaches. Analgesic background pain medication (n=15,211, 100%) and analgesic rescue therapies (n=13,911, 91.5%) were among the most frequently mentioned treatment approaches, followed by physiotherapy (n=13,111, 86.2%), massage (n=11,140, 73.2%), homeopathy (n=9,707, 63.8%), injection treatments (n=8,895, 58.5%), acupuncture (n=8,714, 57.3%), dietary measures (n=8,319, 54.7%), psychotherapy (n=7,942, 52.2%) and TENS (n=7,805; 51.3%). 7,191 patients (47.3%) stated that they had taken part in multimodal pain therapy treatment (MMST) as inpatients and 5,612 (36.9%) as outpatients.

The spectrum of long-term drug therapy included all available treatment options known in pain medicine as well as a whole range of rather unusual (but discussed in “fibromyalgia circles”) alternative therapies (see table 4, part 2). Treatment with non-opioid analgesics was documented by 11,609 patients (76.3%), treatment with NSAIDs by 11,696 patients (76.9%), information on low-potency opioids was found in 12,065 patients (79.3%) and 12,006 patients (78.9%) documented the use of at least one potent opioid analgesic. In addition, 5,141 patients (33.8%) documented the use of at least one cannabinoid, 11,650 patients (76.6%) those of at least one antiepileptic and 14,266 (93.8%) the use of at least one antidepressant. 14,670 patients (96.4%) also stated that they had had experience with at least one drug/active ingredient that tends to be rarely administered or unusual in pain medicine. Across all pharmacotherapeutic options, the patients evaluated in this study documented the use of an average of 11.3±2.7 (median 11, range 3-22) different treatments, with six out of ten patients (n=9,179, 60.3%) stating that they had taken at least 11 different pharmacotherapies, and one in five patients (n=3,055, 20.1%) even at least 14 (Table 4).

Table 4a:Treatment characteristics (part 1).

Table 4b:Treatment characteristics (part 2: background pain medication).

Table 4c:Treatment characteristics (part 3: rescue pain medication).

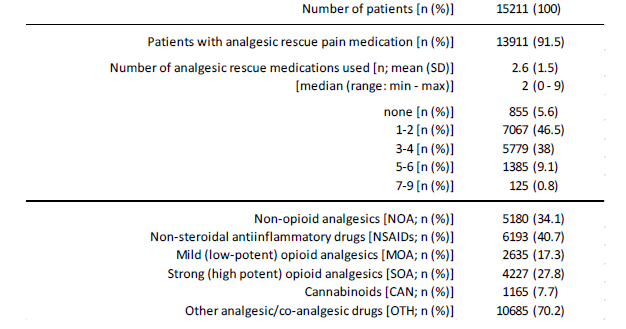

In addition, 13,911 patients (91.5%) also reported the use of pharmacological emergency therapies to a considerable extent (see table 4, part 3). 5,180 patients (34.1%) documented the use or application of an emergency drug therapy with at least one non-opioid analgesic, 6,193 patients (40.7%) documented an emergency drug therapy with at least one NSAID, 2635 (17.3%) documented the use of at least one MOA, and 4,227 documented the use of at least one SOA, 1,165 the use of at least one cannabinoid and 10,685 patients (70.2%) the use of at least one drug/active substance that tends to be administered rather rarely or is unusual in pain medicine. Across all pharmacotherapeutic options, patients reported the use of an average of 2.6±1.5 (median 2, range 0-9) different emergency therapies. Only 855 patients (5.6%) stated that they had not used any emergency therapy to date.

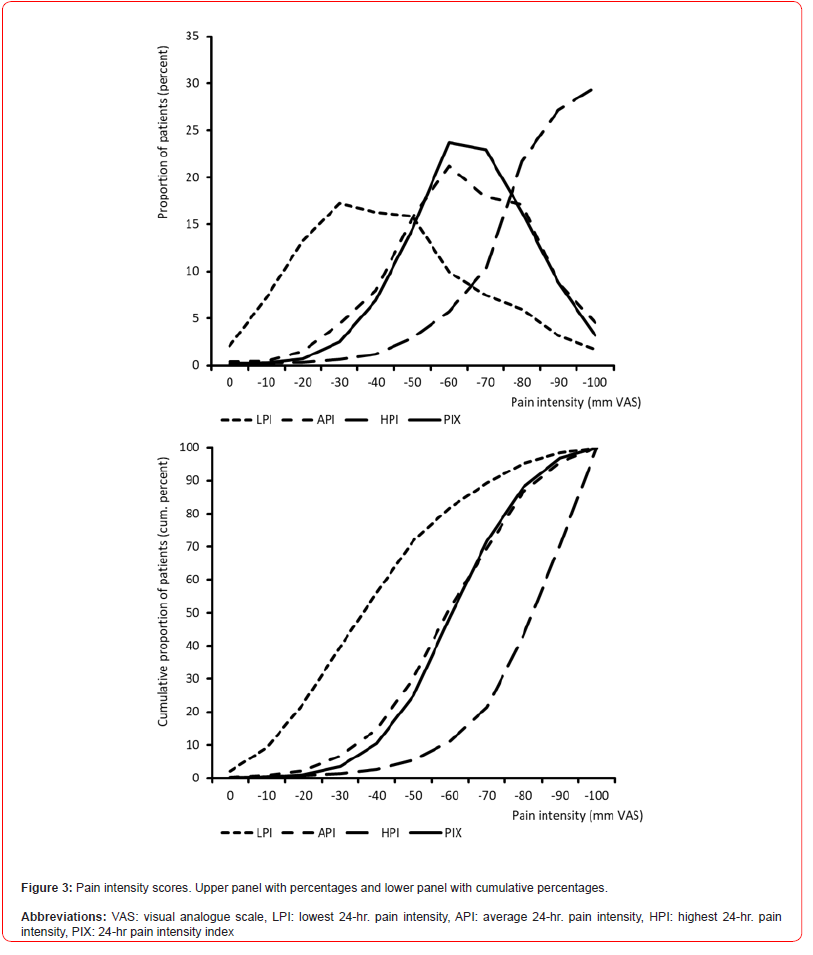

24-hour pain intensities

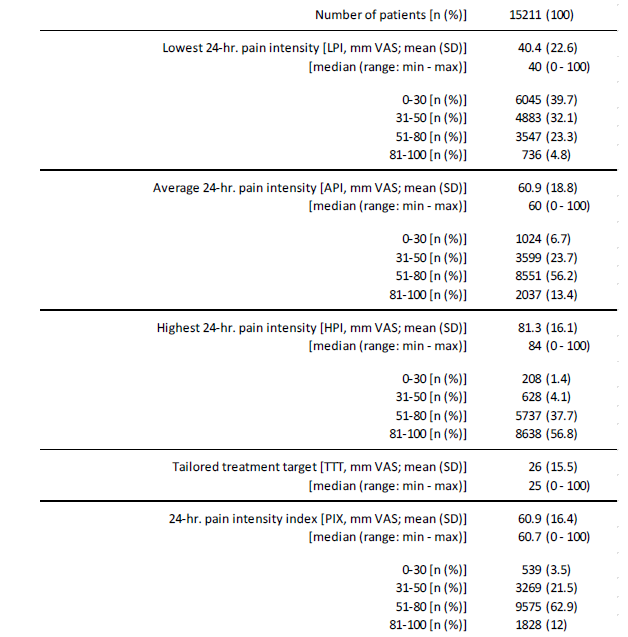

Information on the pain intensity characteristics of FMS patients are given in table 5. The lowest 24-hr pain intensity (LPI) was reported on average as 40.4±22.6 (median 40, range 0-100) mm VAS. With 6,045 (39.7%), four of ten patients documented pain intensity values of 30 mm VAS or less; only 309 patients (2.0%) stated that they experienced completely pain-free episodes, at least temporarily. Average 24-hr. pain intensity (API) was reported as 60.9±18.8 (median 60, range 0-100) mm VAS. With 69.6% (n=10,588) every seventh patient documented pain intensity values of more than 50 mm VAS, with 13.4% (n=2,037) every seventh intensity values of more than 80 mm VAS. The maximum 24-hr. pain intensity was 81.3±16.1 (median 84, range 0-100) mm VAS on average. With 94.5% (n=14,375) nine of ten patients experienced peak pain intensities of more than 80 mm VAS per day, with 56.8% (n=8,638) peaks of more than 80 mm VAS (Table 5).

The calculated 24-hour pain index (PIX) of the patients was 60.9±16.4 (median 60.7, range 0-100) mm VAS on average. With 75.0% (n=11,403), PIX scores were above 50 mm VAS in three quarters of all patients and in one of eight FMS patients (12.0%; n=1,828) PIX scores were regularly above 80 mm VAS. The tailored treatment target (TTT) – as a subjectively defined individual treatment goal for any pain-relieving countermeasures, was 26.0±15.5 (median 25) mm VAS. The average deviation between PIX and TTT was -34.9±17.2 (median 35, range 50 to -100) mm VAS - only 358 patients (2.4%) documented PIX values lower than their treatment goals.

Table 5:Pain intensity characteristics.

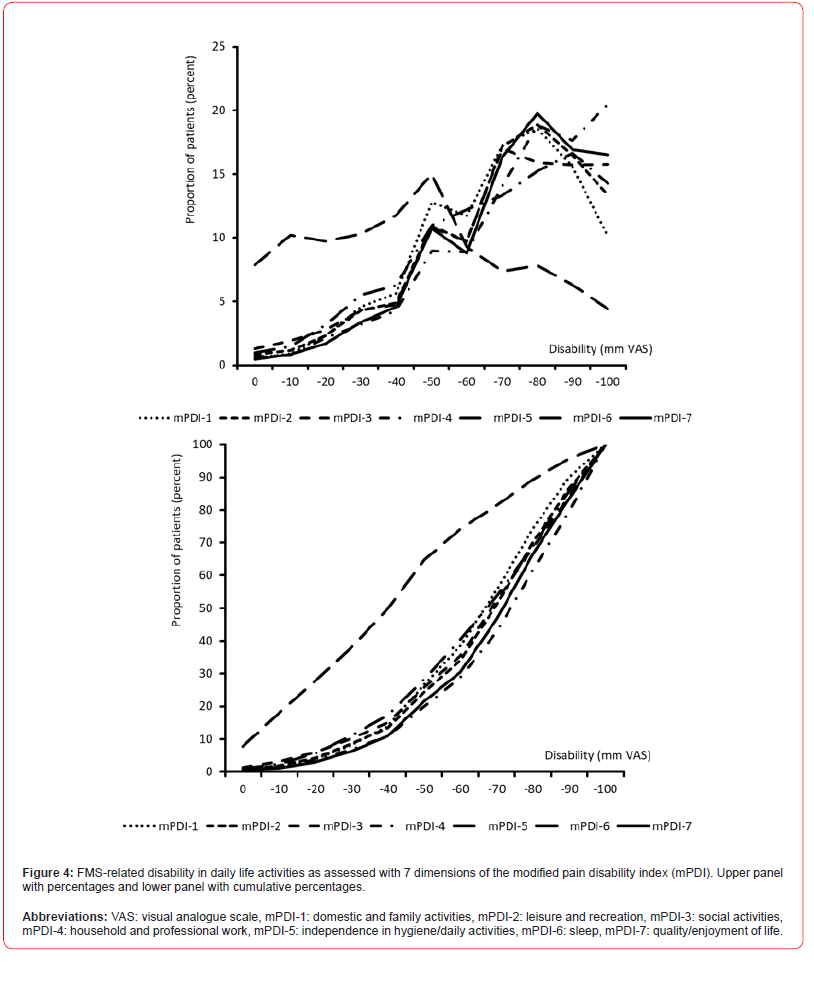

Pain-related disability in daily life activities (mPDI)

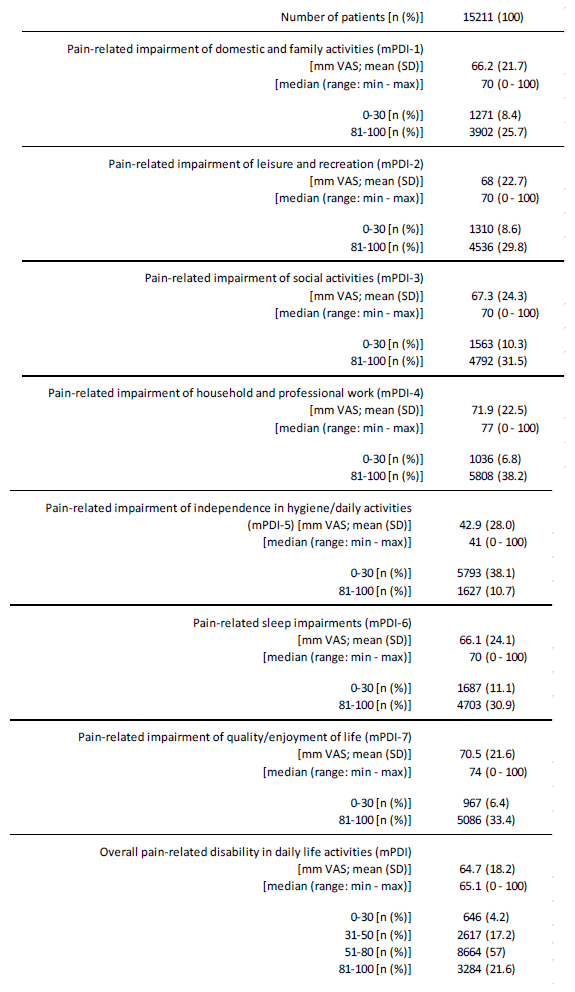

The patient reported overall extent of pain-related disabilities in daily life was 64.7±18.2 (median 65.1, range 0-100) mm VAS on average (see table 6). 78.5% of all patients (n=11,948) reported severe impairment with impairment values above 50 mm VAS, 21,6% (n=3,284) extreme disabilities with values above 80 mm VAS, and only 646 patients (4.2%) minor FMS-related disabilities with mPDI scores of 30 mm Vas or even less (table 6).

The extent of FMS-related impairments in the different dimensions of daily life was largely comparable - with the exception of independence in personal hygiene and basic routine activities (mPDI- 5) at 42.9±28.0 - and ranged on average from 66.2±21.7 (domestic and family activities; mPDI-1) to 70.5±21.6 (quality/enjoyment of life; m PDI-7) mm VAS. Accordingly, the proportion of severely or extremely impaired patients in the various mPDI areas was also comparable and averaged ~ 30%.

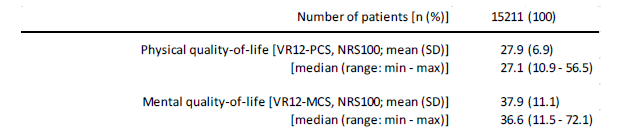

Quality-of-life

The physical quality of life was reported by the evaluated FMS patients with reference to the VR12 Physical Component Scale (PCS) with a mean of 27.9±6.9 (median 27.1, range 10.9-56.5; see table 7). 96.2% of all patients (n=14,627) reported conspicuously low VR12 PCS scores that were more than two standard deviations below the normal range. With reference to the VR12 Mental Component Scale (MCS), the patients evaluated reported an average mental quality of life of 37.9±11.1 (median 36.6, range 11.5-72.1). 70.0% of all patients (n=10,652) reported remarkably low VR12 MCS scores more than two standard deviations below the normal range (table 7).

Table 6:Disabilities in daily life activities (mPDI).

Table 7:Physical and mental quality-of-life (VR12-PCS/MCS).

Mood disturbances

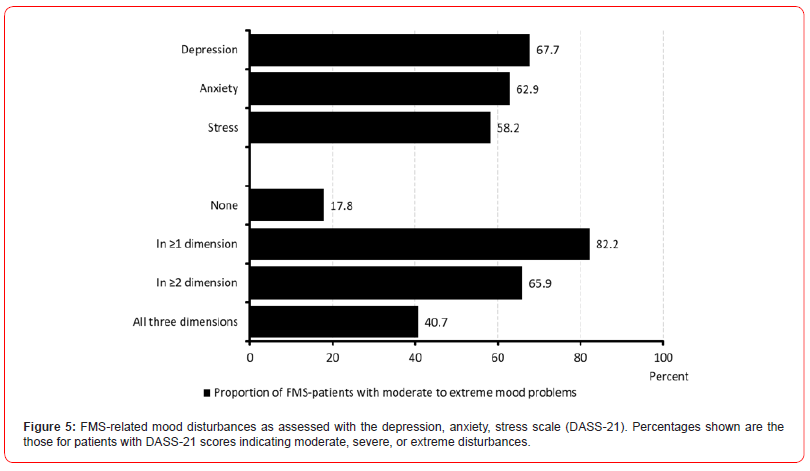

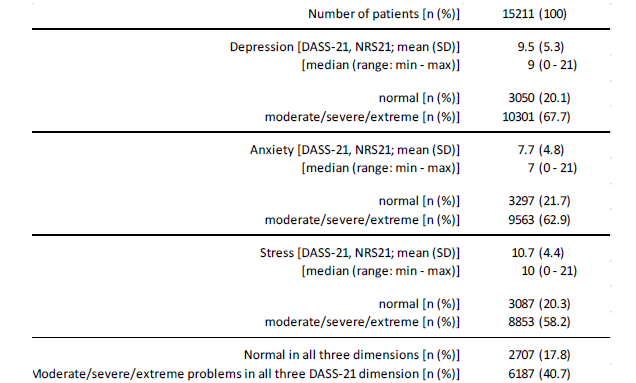

With reference to the German version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), the patients documented an average level of depression of 9.5±5.3 (median 9, range 0-21; table 8). Two thirds of patients (67.7%, n=10,301) reported at least moderate depressive symptoms, and four out of ten patients (40.4%, n=6,147) at least severe depression scores. The reported level of anxiety was on average 7.7±4.8 (median 7, range 0-21); six out of ten (62.9%, n=9,563) reported at least moderate anxiety scores, five out of ten (47.7%, n=7,250) patients at least strong anxiety values. The average stress levels in our FMS population was reported to be 10.7±4.4 (median 10, range 0-21); with 58.2% (n=8,853) nearly six of ten FMS-patients reported at least a moderate, every fourth (27.7%, n=4,218) at least severe stress levels. Only 1 of 6 patients with FMS (n=2,707, 17.8%) documented inconspicuous point scores in all three evaluated dimensions of the DASS-21, whereas four of ten (40.7%, 6,187) showed moderate to extreme mood problems in any three DASS-21 domains (table 8).

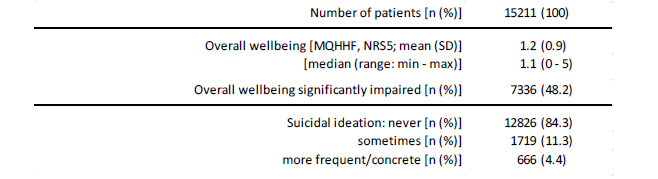

Overall wellbeing and suicidal ideation

Overall wellbeing – as evaluated with the Marburg questionnaire on habitual health feelings, MQHHF) was 1.2±0.9 on average. Nearly half of patients (48.2%, n=7,336) reported point scores ≤1 on the NRS-5 indicating a significant as well as clinically relevant impairment of their overall wellbeing (see table 9).

Table 8:Mood disturbances (DASS-21).

Table 9:Overall wellbeing (MQHHF) and suicidal ideation.

With 15.7% (n=2,385), nearly every sixth FMS-patient stated suicidal thoughts – at least sometimes – due to the underlying chronic pain/FMS condition; 4.4% (n=666) even “more frequently” or “specifically”.

Fibro-fog

As part of a secondary data analysis, the available patient data was evaluated for the presence of possible indications or free-text statements of suspected “fibro-fog” within the German Pain Questionnaire, i.e. the presence of various cognitive impairments. In 13.8% (n=2,099) of all evaluated patient data sets, there were indications of the presence of mnestic impairments, 18.2% (n=2,767) of memory impairments and 16.0% (n=2,434) of thought process impairments. Overall, four out of ten patients in the present data set (n=5,952, 39.1%) showed evidence of fibro-fog with different combinations of the aforementioned search parameters.

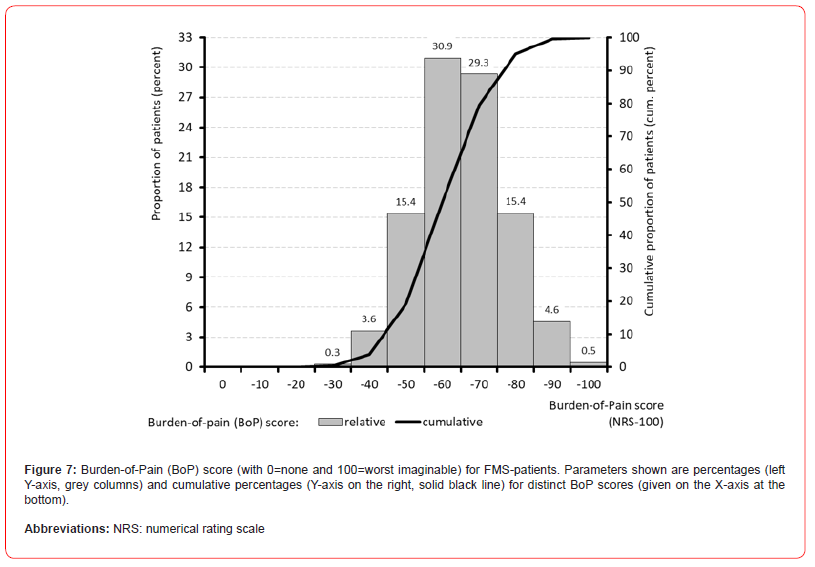

Global burden of FMS

The calculation of the global FMS burden of pain (BoP) index resulted in an average index score of 60.2±11.8 (median 59.9, range 21.8-96.9). With 19.3% (n=2,937), only one in five patients had a BoP index value of 50 or less. Almost half of all patients (49.8%, n=7,569) showed values above 70 and one fifth of patients (20.4%, n=3,107) even showed BoP index values above 80 - as an expression of extremely severe FMS-related burden in daily life (see Figure 7).

Discussion

The present study evaluated the effectiveness of the revised phenomenological ACR criteria for the identification of patients with FMS within a depersonalized mirror of patients registered within the German Pain e-Registry and characterized the biopsychosocial burden of those patients positively identified. To our knowledge, this study is the largest systematic evaluation of the biopsychosocial symptoms of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome conducted worldwide to date. Our results impressively demonstrate the complex spectrum of the multidimensional impairments associated with this chronic pain disorder. Fibromyalgia-related pain, the associated physical disabilities, and impairments in participation in daily life activities, the psychological complaints and, last but not least, the cognitive impairments have an exceptionally high impact on those affected and thus distinguish fibromyalgia from other chronic pain syndromes.

In view of the extent of these impairments, the considerable duration of the disease and the availability of simple phenomenological diagnostic criteria suitable for everyday use (such as the revised 2016 ACR criteria), it is surprising that one in seven of those affected in our collective has not yet been diagnosed with fibromyalgia but with a considerable number of other types of chronic pain. This may be an expression of the (false!) view still prevalent among many physicians that FMS is a diagnosis of exclusion and that they are on an almost endless journey with their patients, gradually ruling out every alternative diagnosis/cause, no matter how vague (but theoretically possible). For many sufferers, this endless search for the cause of their complaints without a concrete confirmatory diagnosis gradually becomes an ever-increasing problem, because the accumulation of knowledge about all the illnesses that they do not have ultimately does not solve the problem of knowing what illness they have. Particularly for these cases, the revised FMS classification criteria of the ACR offer a real alternative and enable an early (re)change from the search for the cause to rational treatment.

It is also surprising that, despite the knowledge that has now been available for some time about the specific genesis of fibromyalgia syndrome and the known low response of the underlying central functional disorders to purely symptomatic analgesics, the most frequently used forms of therapy come from the field of systemic symptomatic pharmacotherapy, while psychologically oriented causal therapy methods - such as cognitive behavioral therapy, talking therapies, progressive muscle relaxation, biofeedback, etc. - were used considerably less frequently.

All of this leads first of all to the realization that - despite all the progress already described - knowledge of the causes of fibromyalgia and the resulting consequences with regard to sensible therapeutic procedures is inadequate, not only among treating physicians but also in the healthcare system in general. There is therefore an urgent need for suitable educational campaigns, information materials and, above all, simple practice guidelines on the revised ACR criteria in order to identify suspected cases as early as possible under everyday conditions and refer them to specialized, holistic pain medicine care. In contrast to the information known from the literature, it is surprising that in almost a third of the patients evaluated by us, the first manifestation of symptoms appears before the age of 30 years, and in almost 7% even before the age of 18 years – i.e. much earlier than usually assumed. This means that the manifestation of FMS as a primarily chronic nociplastic pain syndrome in a significant proportion of those affected coincides with a developmental phase with increased neuronal plasticity due to physiological maturation processes, which not only has numerous implications with regard to the severity and multifaceted nature of the FMS phenotype, but also raises questions about the possible transition from functional to structural causes. Juvenile onset FMS (jFMS) is an even less poorly understood facete within the spectrum of FMS manifestations. Available literature shows that patients with jFMS present with higher daily pain intensities and even poorer physical functioning, combined with greater depressive and anxiety symptoms [26,27]. In view of these findings and the more serious consequences of FMS in this age group in particular, it therefore seems urgently necessary to distribute appropriate information material on FMS to pediatricians and physicians caring for adolescents and younger adults and to integrate information campaigns on FMS into the curriculum in schools and school-related institutions, knowing that it may be difficult to address this issue adequately [28].

Among the large number of striking findings with regard to the breadth and severity of the physical and mental impairments, the astonishingly high proportion of patients (15.7%) who, when asked about their complaints, stated that they wanted to take their own lives because of their long-lasting and severely impairing complaints - or at least consider taking such a step - stands out in our view. In view of the large number of drug and non-drug therapy methods that have obviously been used more or less unsuccessfully (but with probably significant side effects?), this is a critical warning signal especially against the background of the additional triggers that are present in many of those affected and their - also obviously - inadequate psychotherapeutic targeting. Patients with FMS must not only be recognized much earlier, and their symptoms diagnosed more quickly, but rational treatment concepts must also be introduced more promptly. This is the only way to avoid the dramatic consequences of many years of inadequate and frustrating treatment attempts for those affected and to reduce iatrogenic and/ or systemic factors that promote chronicity and drive suicidal ideation as a relevant co-factor. A recent meta-analysis evaluated the risk of suicidal ideation and attempts in FMS patients and identified several risk factors, such as disease severity, employment status, drug dependence, pain intensity, impaired quality-of-life, and co-morbidities (in particular depression, anxiety, poor sleep), that also characterized the clinical presentation of the patients in our study [29]. The majority of the factors mentioned can certainly be attributed primarily to the underlying FMS and its possible triggers. Nevertheless, in view of the high number of frustrating (and unnecessary, because they follow the wrong concepts) treatment attempts and the generally inadequate (rapid) positive diagnosis and the associated (sometimes decades-long medical history), it should at least not go unmentioned that inadequate medical care (especially the uncritical prescription of ineffective pain medication) also contributes to this.

Analgesics and non-analgesic co-analgesics (like antidepressants or anticonvulsants) play a particular role in many chronic pain disorders, and it is not uncommon for them to be able to alleviate the extent of the physical and mental impairments of those affected - when used rationally and in a mechanism-oriented manner - at least to such an extent that these patients are able to actively participate in private, social, and professional life. The fact that these pharmacotherapeutic strategies are only partially successful in patients with fibromyalgia is demonstrated by the considerable impairments of those patients we evaluated with regard to their participation in daily life, their physical and mental quality of life, their general well-being and especially their strikingly depression, anxiety, and stress disorders. For this reason, the inadequate response of pain and pain-related impairments should always be a reason for physicians to question the rationale of their therapy, to (re)evaluate the underlying pathophysiology and, if necessary, to consider other (non-drug and drug) alternatives. The fact that this obviously did not happen to the extent that would be desirable in the group of FMS patients we evaluated should give us reason for thought and ultimately also prompt us to question the basic (often monomodal) pain therapy approach and to establish multimodal holistic therapy concepts much earlier (than has been the case to date).

Strength and Limitations

An important strength of the German Pain e-Registry is its focus on patient-reported data, while at the same time the entries are validated by experienced pain specialists. Another strength is the dual aim of generating data for research, but also supporting patients and physicians in their documentation and assessment of pain in everyday practice, and the possibility of sharing all information, which increases patient engagement. It should be noted that registry data can never be representative of the prevalence of a disorder in the general population. This is because, firstly, people with fibromyalgia who do not consult a doctor are not included. Secondly, the German Pain e-Registry focuses on centers with a special interest in pain, which keeps the data quality high, but results in a significant selection bias towards more severely affected patients. This problem is challenging, as it are mainly physicians with a special interest in pain who are willing to participate in such a registry. On the other hand, registry data are always observational. The resulting risks of bias include the lack of random assignment to therapies and the possible influence of treatment success on patients’ willingness to participate. What’s more, the obvious disadvantage of the fundamental lack of a control approach - especially for day-to-day practice - conceals the great advantage of low-threshold use. In this way, physicians and patients can document and evaluate what best meets their individual needs and requirements, and do not have to worry about externally defined framework conditions. This is a major advantage in improving individual patient care.

Usage of the German Pain e-Registry is free of charge for both physicians as well as patients irrespective of their specialty or insurance status and the implementation of the underlying online system in daily practice routine is easy and its use is extremely timesaving for patients as well as practitioners and assistants thanks to the integrated evaluation routines and support services.

Conclusion

Fibromyalgia syndrome is a complex disorder of central signal processing and a disturbed signal generation that is associated with chronic wide-spread pain and a broad spectrum of biological, psychological, and social impairments. Despite suitable and well-validated clinical screening instruments - in the form of the revised ACR criteria - the diagnosis is made (too) late in many cases, treatment is frustrating and predominantly monomodal medication-based, and the resulting additional impairments are accepted (neglected?) by physicians. The consequences for those affected are considerable and ultimately lead to the emergence of the full picture of a severe chronic pain syndrome with complete restrictions in all areas of physical and mental well-being, as a result of which many sufferers seriously consider suicide or at least struggle with suicidal ideations - which must ultimately be understood as the ultimate cry for help and an expression of a (possibly systemic) failure of medical care. The cross-sectional analysis of the biopsychosocial burden presented by us raises numerous questions that cannot (yet) be answered here (such as gender differences or the influence of the age of onset on the further course of the disease or the fundamental differences to other - more nociceptive or neuropathic - chronic pain disorders, etc.), and which have to be investigated in subsequent studies However, the present study already proves that the depersonalized evaluation of routine data from standard care via suitable register structures - such as the German Pain e-Registry - not only enables a quantitative approach but offers also qualitatively new perspectives for research into chronic health disorders.

Author Contributions

MAU was primarily responsible for the study concept and the biometrical analyses performed, and he also guarantees for the validity of the data as well as the integrity of the results. MAU also drafted the initial version of this manuscript and prepared all necessary tables and figures. All co-authors have made a substantial contribution to the work reported, be it conception, design, conduct, data interpretation, or all of these; have been involved in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; have given final approval for the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted; and agreed to accept responsibility for all aspects of this work.

Funding

This research as well as the manuscript preparation were funded by unrestricted scientific grants of the German Pain Association.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

Due to restrictions of the EU data protection guideline and the standard operating procedures of the German Pain e-Registry the original datasets generated and analyzed for the current study are not available for external research.

References

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Marotto D, Atzeni F (2020) Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol 16(11): 645-660.

- Jones GT, Atzeni F, Beasley M, Flüß E, Sarzi-Puttini P, Macfarlane GJ (2015) The prevalence of fibromyalgia in the general population: a comparison of the American College of Rheumatology 1990, 2010, and modified 2010 classification criteria. Arthritis Rheumatol 67(2): 568-575.

- Wolfe F, Walitt B, Perrot S, Rasker JJ, Häuser W (2018) Fibromyalgia diagnosis and biased assessment: sex, prevalence and bias. PLoS One 13(9): e0203755.

- McDonald M, DiBonaventura M, Ullman S (2011) Musculoskeletal pain in the workforce: the effects of back, arthritis, and fibromyalgia pain on quality of life and work productivity. J Occup Environ Med 53(7): 765-770.

- Arnold LM, Gebke KB, Choy EH (2016) Fibromyalgia: management strategies for primary care providers. Int J Clin Pract 70: 99-112.

- Galvez-Sánchez CM (2019) Depression and trait-anxiety mediate the influence of clinical pain on health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia. J Affect Disord.

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, et a. (1990) The American College of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 33(2): 160-172.

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, et al. (2010) The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res 62: 600-610.

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DI, Häuser W, et al. (2016) Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum 46: 319-329.

- World Health Organization (1992) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Problems. ICD-10. Geneva: WHO.

- Treede R_D (2022) Chronic musculoskeletal pain: traps and pitfalls in classification and management of a major global disease burden. Pain Rep 7(5): e1023.

- Picard F, Friston K (2014) Predictions, perception, and a sense of self. Neurology 83: 1112-1118.

- Barrett FL, Simmons WK (2015) Interoceptive predictions in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 16: 419-429.

- Peters A, McEwen BS, Friston K (2017) Uncertainty, and stress: Why it causes diseases and how it is mastered by the brain. Progress Neurobiol 156: 164-188.

- Bannister K, Dickenson AH (2017) The plasticity of descending controls in pain: translational probing. J Physiol 595: 4159-4166.

- Hird EJ, Charalambous C, El-Deredy W, Jones AK, Talmi D (2019) Boundary effects of expectation in human pain perception. Sci Rep 9: 9443.

- Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, Litteljohn G, Usui C, Häuser W (2022) Chronic primary musculoskeletal pain: a new concept of non-structural regional pain. PAIN Rep 7:e1024.

- (2023) Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust:

https://www.torbayandsouthdevon.nhs.uk/uploads/quick-guide-to-fibromyalgia-scoring.pdf.

- German Pain Association (2023) Manual for the German Pain Questionnaire (in German). https://www.schmerzgesellschaft.de/fileadmin/pdf/DSF_Handbuch_2020.pdf. The National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians and the regional Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians. Agreement on quality assurance measures according to § 135 Para. 2 SGB V for pain therapy care of patients with chronic pain. Last assessed online via https://www.kbv.de/media/sp/Schmerztherapie.pdf on December 31, 2023. German.

- Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ (1992) Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain 50(2): 133-149.

- Schuler M, Schwarzmann G (2020) The Mainz Pain Staging System is also suitable for grading chronic pain in inpatient geriatric patients]. Schmerz. Aug 34(4):332-342. German.

- Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Krause S (1990) The Pain Disability Index: psychometric properties. Pain 40: 171-182.

- Kazis LE, Miller DR, Skinner KM, Lee A, Ren XS, et al. (2004) Patient-reported measures of health: the Veterans health study. J Ambulatory Care Manage 27: 70-83.

- Hüppe M, Schneider K, Casser H-R, Knille A, Kohlmann T, et al. (2022) Characteristic values and test statistical goodness of the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) in patients with chronic pain : an evaluation based on the KEDOQ pain dataset. Schmerz 36: 109-120. German.

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1996) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation of Australia, Sydney.

- Nilges P, Essau C (2015) Depression, anxiety and stress scales: DASS–A screening procedure not only for pain patients. Schmerz 29: 649-657. German.

- Kashikar-Zuck S, Cunningham N, Sil S, Bromberg MH, Lynch-Jordan AM, et al. (2014) Long-term outcomes of adolescents with juvenile-onset fibromyalgia in early adulthood. Pediatrics 133(3): e592-e600.

- Türk C, Sahin F (2020) Prevalence of juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome among children and adolescents and its relationship with academic success, depression and quality of Life, Çorum Province, Turkey. Arch Rheumatol 35(1): 68-77.

- Peterson EE, Yao C, Sule SD, Finkel JC (2023) The Challenges of Identifying Fibromyalgia in Adolescents. Case Reports in Pediatrics 2022 ID 8717818 https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8717818. Last assessed online on December 31, 2023.

- Adawi M, Chen W, Bragazzi NL, Watad A, McGonagle D, et al. (2021) Suicidal behavior in Fibromyalgia patients: rates and determinants of suicide ideation, risk, suicide, and suicidal attempts—a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of over 390,000 fibromyalgia patients. Front Psychiatry 12: 629417.

-

Michael A. Überall*, Heinrich Binsfeld, Dorothea Fago, Thorsten Lücke, Silvia Maurer, Norbert Schürmann and Johannes Horlemann. Bio-Psycho-Social Burden of Patients With Fibromyalgia – Results of A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Depersonalized Data Provided by the German Pain E-Registry. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 17(1): 2024. ANN.MS.ID.000902.

-

Acute Polyradiculoneuritis, Neurology, Guillain-barre; Fann teaching hospital, neuropathy, cranial nerves, immunotherapy, Neuroscience, neurogenic syndrome, epidemiological, Dysphonia.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.